Did Christmas Copy Paganism?

The Celebration Emerged Organically in the Largely Decentralized, Pre-Constantine Church

The Early Church was much less of a top-down, steeply hierarchical community than what the largest Christian denominations look like in 2023.

Christmas emerged quite organically in this more “anarchist” environment.

No date for Jesus’ birth is given in the Bible, and the formalization of Christmas during the post-Constantine period leads many to think Christmas actually started in the fourth century A.D.

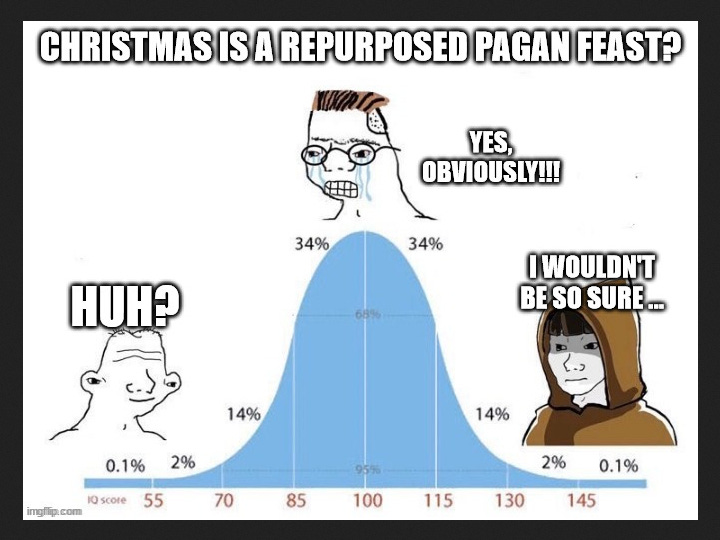

There are also some rough similarities between Christmas and non-Christian celebrations during late December. This “pattern matching” leads many to conclude that Christmas is basically a winter solstice celebration, borrowing its key elements from paganism.

(And, yes, I actually made this meme shown above specially for this Substack post! It’s a bridge I didn’t know I’d ever cross — into the land of making interwebbies memes — but here we are.)

I’m always skeptical of claiming the origins of something deeply Christian are found in the Constantine and post-Constantine Church. I’m very critical of some regressive changes that occurred in the Church due to Constantine and say so in Station 2 of the Good Neighbor, Bad Citizen book.

Christmas pre-dates the flood of paganism into the Church

Turns out, Christmas traces to before Constantine, before the Official Church devolved into fanatically political hierarchy and justifications for violence that resembled paganism.

I recommend two articles to explain this in depth:

Finally, in about 200 C.E., a Christian teacher in Egypt makes reference to the date Jesus was born. According to Clement of Alexandria, several different days had been proposed by various Christian groups. … [T]he first mention of a date for Christmas (c. 200) and the earliest celebrations that we know about (c. 250–300) come in a period when Christians were not borrowing heavily from pagan traditions of such an obvious character. (McGowan)

The best evidence for early Christians placing Christmas on Dec. 25 involves “integral age.” It’s a modern term for a belief that a holy person enters the world and leaves the world at the same time of year, so the person’s lifespan is an “integer” — a whole number — of years.

For more on the “integral age,” I recommend another article, plus an ancient text that McGowan cites (the Rosh Hashanah from the Babylonian Talmud):

Christ’s birth is likely a reflection of Christ’s death

The early seekers of Jesus’ date of death landed in the year we call 29 A.D./C.E., on March 25.

We now know this date is wrong …

[T]his is impossible: 25 March 29 was not a Friday, and Passover Eve in A.D. 29 did not fall on a Friday and was not on March 25th, or in March at all. (Tighe)

… but they apparently didn’t know it back then.

After all, they had Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and possibly other calendars all in use, each with its own months and years! Things we take for granted in 2023 — like being confident that pretty much everyone knows it’s 2023! — weren’t valid 18 centuries ago.

So they accepted March 25 for Jesus’ conception/death date. Add nine months, and you hit Dec. 25.

Those translating into the Greek calendar made an additional mistake in converting the date of Passover in 29 A.D. and settled on April 6 as Jesus’ day of death, leading to Jan. 6 as their date for Christmas.

Embrace the real purpose

In a hyperconnected world with a centralized Church, all these errors could be easily, quickly fixed.

But the logistical difficulties of the past show us something more important than centralized, top-down control, and more meaningful than cold compliance and cataloging of citizens.

These more distributed communities of the Early Church tried to create a celebration, the date of which conveyed their beliefs about holiness and the connection between life and death.

And their “mistakes” serve as the evidence that they aimed to define and refine a truly Judeo-Christian perspective, rather than the repackaged paganism that would (sadly) infect later eras.

I think they succeeded! And I encourage everyone to revisit the Early Church’s organic, grassroots, decentralized, good-neighbor-bad-citizen characteristics and the wonderful gifts — including Christmas — they gave to future generations.

What do you think of these rarely discussed histories? What are your impressions of this essay? Share your thoughts in the Comments below!

I took part in a conversation recently that started with a meme about Early settlers in Concord banning Christmas because it was "pagan".

I'm of the opinion that the Pagan's weren't a big enough influence in the New World for them to worry about it, but they were against the Paganism found in the Catholic Church.

I also know that during this exact same time they hung my 11th Great Grandmother in Boston for refusing to stop spreading Quaker ideas. It seems more likely to me that their primary concern was that Christmas celebrations were simply too rambunctious and didn't promote the right way of celebrating such an important event. Not that the holiday itself was of Pagan origin.

So where they worried about Pagans and did they believe Christmas celebrations were themselves Pagan in 1630 or where they just anti-any-religion but their own and didn't want to see anyone having a good time?