When the ‘Nation’ No Longer Matters

Long Before Canadian Pols Made the Term Famous, the U.S. Was a ‘Postnational’ State

If you enjoy this article, please click Like (❤️) to help others find my work.

This one required a bit of research and learning for me.

“Postnational” talk crept into the news cycle due to the Canadian elections two days ago. I’m no fan of government, so that means I don’t get excited about any sort of voting/elections nor the high holyday when most of the ritual is supposed to occur.

But the “postnational” controversy intrigued me, especially since I don’t recall encountering the term “postnational” until recently.

So, I did what I thought prudent: I looked up how it was used in context and what it is generally agreed upon to mean, which led to a deeper dive into word origins and historical usage.

In the days leading up to the elections, Canadian Member of Parliament (MP) and leader of the Bloc Québécois party in Quebec, Yves-François Blanchet, dubbed Canada, “an artificial country with very little meaning called Canada.”

When questioned about it, he explained that he considered Quebec, with its dominant French language and culture, a “proud nation,” in contrast to the postnational sense of Canada at-large.

Blanchet referenced former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2015 interview with the New York Times — rehashed in Canadian newsmedia — in which Trudeau said of Canada:

[Canada is the] first postnational state. … There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada. … There are shared values — openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice.

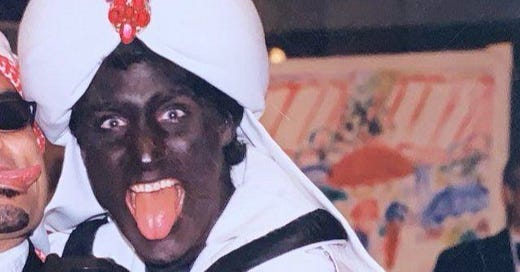

Those who know Trudeau’s former bout with dressing in blackface (pictured at top of article) and the way he ruled, especially during the COVID hoax, can rightly question how much Trudeau really believes in genuine tolerance, “openness, respect, compassion, … justice.” But he did pay lip service to those ideas.

Trudeau had echoed an even earlier P.M., Jean Chrétien, who used “postnational” alongside “multicultural” and “open to the world” to describe Canada in a 2000 speech.

Chrétien and Trudeau meant “postnational” as a compliment. Blanchet used it lukewarmly and matter-of-factly. Their critics saw the term as an insult to what they considered to be a strong sense of nationhood.

So, with people arguing over national vs. postnational, what makes a “nation,” anyway?

Etymology of ‘nation’

While “nation” is often simply a synonym for a large political state, its Latin origins suggest something pre-political — “birth, origin; breed, stock, kind, species; race of people, tribe,” literally “that which has been born” — and related to other words that have the “natus” root: natal, native, nature.

The political connotation of a large state, in contrast to smaller political divisions at the local and provincial levels, emerged later. But this “national” sense still carried an expectation that its members had some common ancestry and generational connection to a place inhabited.

In this understanding, Canada and most other Western “nations” have been trending postnational for a long time, since travel became easier and more widely accepted.

Charles Mann wrote that the voyages to what Europeans called the New World started this upheaval of human development, in his book, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created.

Europe and those places encountered by European explorers, traders, and conquerors were on the road to postnationalism even before the colossal, modern nation-states emerged.

As such, the United States of America was always postnational, cobbled together beginning in the late 1700s from diverse settlers who had sometimes overrun existing populations and sometimes forcibly brought others across the ocean as slaves.

Perhaps no one put it better than the writers of the movie, Stripes, in which John Winger (played by Bill Murray) gives his fellow enlisted men a history lesson wrapped in a pep talk (watch at this link or embedded below):

We’re all very different people. We’re not Watusi. We’re not Spartans. We’re Americans, with a capital “A”! You know what that means? Do you? That means that our forefathers were kicked out of every decent country in the world! We are the wretched refuse. We’re the underdog. We’re mutts.

A good thing

Postnationalism seems to be a positive development.

It’s a behavior and mindset that anarchists/voluntarists should welcome. If human interaction is supposed to be done by consenting individuals without deferring to identity politics and collectivism, then the idea of political privileges based on nationality must wither away.

Christians should also be wholeheartedly postnational (or, better yet, never-national). The Early Church quickly learned to evangelize without discriminating based on a person’s origins. Christians were famous (or infamous, depending on who you ask) for crossing political boundaries, intermingling, and building shared culture beyond ethnic, racial or territorial confines.

Later Christians, unfortunately, betrayed the Gospel message by turning to the very same imposed, hierarchical social order that Jesus undermined. To the extent that those who identify as Christian have fallen into nationalism, imperialism, or any other attempted justifications of violence-based politics, I hope they become “post-” all of that nonsense.

Good citizenship has always been awash in political categorizations like “nationhood,” intended to justify government.

Good neighborliness can’t succumb to such shallow mindsets and deficient ethics.

For one article, at least, I’ll tweak my regular encouragement: Be a good neighbor, even if it makes you a postnationalist.

Post-article, post your Comments!

Had you heard of “postnational” before this week?

Ever seen the movie, Stripes? What’s your take on John Winger’s assessment of Americans?

What are the biggest challenges to anarchism/voluntarism and genuine Christianity posed by nationalism and the attempts to move to something else (postnationalism) while still retaining violence-based politics?

When was the last time you did a deep-ish dive into a new term to learn what it means and where it came from?

Anything else on your mind pertaining to this article’s themes?

Let me know your thoughts below …

—

My book, Good Neighbor, Bad Citizen, is available at:

· Amazon (paperback & Kindle)

· Barnes&Noble (paperback)

· Lulu (paperback)

Find me on X: GoodNeighBadCit

And, as always: Be a good neighbor, even if it makes you a bad citizen.

“Lighten up, Francis!”

Maybe one day we can even get past post-nationalism too.

I only recently heard the term, too. At first blush, I'm like: Yay! An end to nation-states! But of course, that's not what they mean. I think they mean something closer to, "We are bound together by nothing but coercion."

Maybe we can co-opt the term?