‘You’re Not Going Back Far Enough’

A New Book Looks at What Happens When Christians Suffer the Tyranny of Other Christians

If you enjoy this article, please click Like (❤️) to help others find my work.

You may have heard of the of the horror-movie / TV plot element in which a person gets suspicious phone calls, only to discover that “The call is coming from inside the house!”

It was first used in movies in the 1970s, perhaps inspired by a real-life crime in 1950. The phrase is now a popular idiom referring to any situation in which the greatest danger comes from within, rather than an external source.

I thought of this old trope while reading Cody Cook’s newly released book of essays, The Anarchist Anabaptist, published by the Libertarian Christian Institute (LCI). Cook frequently podcasts and writes for LCI, and the book contains six of his LCI articles, plus two he penned for the Foundation for Economic Education, and one each that ran in Reason and Plough magazines.

Two more essays, including the longest and most foundational piece, are brand-new material.

The book explores a variety of historical incidents and movements connected to Anabaptism, a category of Christian denominations that broke from both the Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant reformations of the 16th century.

The story of the early Anabaptists is one of persecution, but not by the various, openly pagan power structures that tried to exterminate the Early Church in the first three centuries A.D.

For the Anabaptists of the 1500s, the violent tyranny emanated from the other nominal Christians who professed, as Cook writes, “that the church must be propped up by the force of government.”

The call was coming from inside the house.

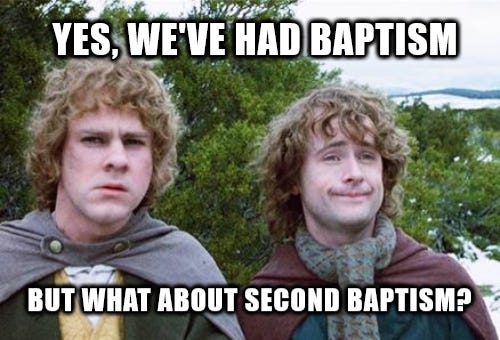

Second — and Third — Baptism

The Anabaptists, whose most well-known contemporary denominations are Mennonites and Amish, harken back to the Early Church, when Christians courageously, righteously defied monopoly-violence institutions we call “governments.”

The sad corrupting of Christianity into the statist “Christendom” occurred during and after the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine (4th Century A.D.), and was perhaps at its worst leading up to the 16th Century (I’ve written about this time period in articles about Joan of Arc).

The people in the early 1500s who became the Anabaptists, took a stern look at a foundational practice: Baptism. As Cook writes in the Preface:

[Anabaptists] were so committed to voluntary faith and freedom of religion that they rejected infant baptism and re-baptized adults, reasoning that babies cannot consent to be Christians. For this unfashionable view, many were given a “third baptism” by their religious enemies: They were taken by force and drowned.

It may look, at first glance, like a petty dispute over a purely spiritual idea. But under Christendom, both Roman Catholic and eventually Protestant, the sacrament of Baptism had suffered a profane corollary: to affirm what we would identify today as a political patriotism and loyalty to the State.

The Anabaptists objected to this use of the sacrament and to the coercive civil authority that Baptism sadly came to reinforce.

From Cook again:

Anabaptists coalesced around certain key ideas: the baptism of sincere believers, nonviolence, separation from the state (in particular its violent functions), and living simply together in community.

In practice, this made Anabaptists largely anarchist in their conception of social order.

Cook’s main thesis is that this anarchism, while radically out-of-step with the Christendom in which it emerged (and still very much opposed to what is today called Christian nationalism), is thoroughly compatible with Jesus’ message as recorded in the four Gospels of the Bible.

I agree wholeheartedly. It’s what “Good Neighbor, Bad Citizen” means.

So, are you …?

Does this make me an Anabaptist?

No.

I have a criticism of the Anabaptists on religious grounds that is very similar to the Anabaptist criticism of what statist “Christians” were doing for centuries.

To me, sacraments are instances of grace — primarily acts of God, and secondarily acknowledgments by humans of these acts of God — that are valid even when practiced by imperfect Church members. A true Baptism, including of an infant who is gracefully welcomed into the Christian community before he or she is able to express such an explicit social connection, never needs to be repeated.

I cognitively empathize with the Anabaptists who were discouraged by the extra-spiritual misuse of Baptism as a government tool. But in claiming the need for a re-Baptism, the Anabaptists seem to still view the sacrament primarily as a gesture of human socio-political origin, redone to emphasize a new socio-political allegiance (or non-allegiance, if you prefer). This is the same misguided, aiming-too-low emphasis that statists were guilty of when assuming citizen-loyalty to the sacrament.

Anabaptists seem to be Christian humanists; my faith is in something more than humanism.

Are the Anabaptists better neighbors than the Christendom fanatics from which they diverged and the modern Christian nationalists who “kneel for the cross and stand for the flag”? It sure looks that way. I’d gladly interact with them.

And for this education in Anabaptist history and their core social practices, I have Cook and his excellent book to thank.

Christians who want to rediscover tradition can learn much from Christian anarchists like the Anabaptists: Seek not the fundamentally fallacious 1700-year slog of Christendom, but rather the truth, beauty, and goodness of the Gospels and the Early Church.

Giving Cook the last word:

Christian nationalists dream of going back to an earlier era, a time when civics and faith seemed inseparable. The response of the Christian anarchist is, “You’re not going back far enough.”

Go back … to the Comments!

What do you know about the Anabaptist history? I admit I knew very little until reading Cook’s new book.

What do you think of modern Christian nationalists?

Ever had “a call coming from inside the house”?

Anything else on your mind regarding this article’s themes?

Share your thoughts below …

—

Find the book, Good Neighbor, Bad Citizen:

Amazon (paperback & Kindle)

Barnes&Noble (paperback)

Lulu (paperback)

Find me on X: GoodNeighBadCit

I love that urban legend. Back when I was teaching high school, I ended the year with a unit on urban legend. This was one of the favorites and it works so much better with cell phones.

Ah, excellent essay!

I’d like to read more about what you mean by and think of ‘Christian humanism,’ a label I rather like.